Climate and Weather Federal forest policy Monkeywrenching forests The 2010 Fire Season

by admin

Big Whoosh

The cold front is blowing by right now here in the Willamette Valley. Trees are swaying, the wind chimes are ringing, and the temperature has dropped 15 degrees. This place is protected by topography from most of the wind, but clouds are winging eastward at high speed, indicating that winds aloft are quite strong.

From the National Weather Service this morning:

URGENT - FIRE WEATHER MESSAGE - NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE

RED FLAG WARNING IN EFFECT FOR NW CALIFORNIA, EASTERN OREGON, EASTERN WASHINGTON, NORTHERN NEVADA, IDAHO, MONTANA, WESTERN WYOMING

LOW RELATIVE HUMIDITIES AND STRONG SOUTHWEST WINDS WILL CREATE CRITICAL FIRE WEATHER CONDITIONS

A RED FLAG WARNING MEANS THAT CRITICAL FIRE WEATHER CONDITIONS ARE EITHER OCCURRING NOW…OR WILL SHORTLY. THESE CONDITIONS WILL CREATE THE POTENTIAL FOR EXPLOSIVE FIRE GROWTH.

Current Red Flag Warning Products [here]

The cold front will pick up speed as it surmounts the Cascades and sweeps across the Columbia Plateau. When it reaches Idaho, ground winds will gust up to 50 mph or more. There the winds will encounter a number of Let It Burn fires — Federal fires that should have been contained weeks ago but instead have been allowed to grow and incinerate America’s priceless heritage forests.

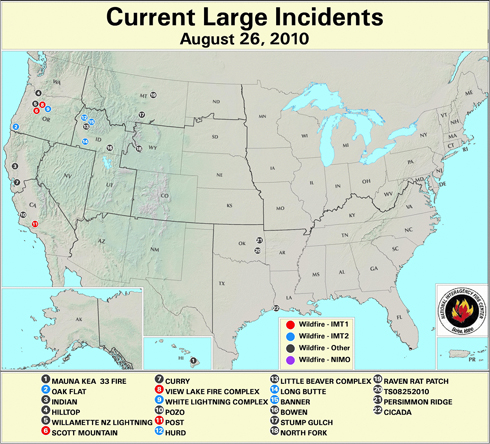

Current Large Incidents Map (click for larger image)

Fires currently burning (some of which are not on the map) include:

Larkins Let It Burn Complex Fires (ID); Clearwater NF; Size: 749 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Scott Mountain Let It Burn Fire (OR); Willamette NF (OR); Size: 935 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Gravel Let It Burn Fire (WY); Bridger-Teton NF; Size: 433 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Hurd Fire (ID); Boise NF; Size: 506 acres; Percent Contained: 15% [here]

Alder Creek Fire (ID); Lolo NF; Size: 425 acres; Percent Contained: 5% [here]

Fire 264 Let It Burn Complex (OR); Mt. Hood NF; Size: 500+ acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Banner Let It Burn Fire (ID); Salmon-Challis NF; Size: 2,077 acres; Percent Contained: 18% [here]

White Lightning Fire (OR); Warm Springs Reservation; Size: 33,016 acres; Percent Contained: 40% [here]

Eight Mile Lake Let It Burn Fire (WA); Okanogan-Wenatchee NF; Size: 119 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Arthur 2 Let It Burn Fire (WY); Yellowstone National Park; Size: 200 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Vernon Let It Burn Fire (CA); Yosemite National Park; Size: 160 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Thunder Let It Burn Fire (WA); Okanogan-Wenatchee NF; Size: 125 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Oak Flat “Appropriate Response” Fire (OR); Rogue River-Siskiyou NF; Size: 4,760 acres; Percent Contained: 75% (allegedly) [here]

Sheep Let It Burn Fire (CA); Kings Canyon National Park; Size: 2,425 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Hopper Let It Burn Fire (WA); Olympic National Park; Size: 385 acres; Percent Contained: 15% (not by firefighters) [here]

Little Beaver Complex Let It Burn Fire (ID); Boise NF; Size: 5,350 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Bighorn Let It Burn Fire (ID); Salmon-Challis NF; Size: 1,128 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Bull Let It Burn Fire (WY); Bridger-Teton NF; Size: 3,539 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

Twitchell Canyon Let It Burn Fire (UT); Fishlake NF; Size: 4,482 acres; Percent Contained: 0% [here]

This is the centennial year of the Great Fires of 1910, and much discussion has taken place about megafires and why, how, and when they arise [here].

From old SOS Forests, the archived version [here]

Palousers

July 24th, 2007

… Today the wind shifted, and a cold, dry front is blowing through right now as I type. The clouds have cleared, the sky is blue, the sun is shining, it’s 60 degrees in the shade at 10 AM, and the wind is from northwest at 15 to 20 mph. That’s what a cold front in July looks and feels like around here.

Whereas the weather here in western Oregon is balmy, across the Cascades to the east something else is happening. The same fronts are blowing across the continental plateau between the Cascades and the Rockies, but with a magnified effect. When southwesterly warm fronts swap places with northwesterly cold and dry fronts over the continent, big winds are generated.

A 15 mph wind in western Oregon can turn into a 50 mph wind on the high deserts of eastern Oregon and Washington, and then it can slam into Idaho and Montana and go sweeping down the other side of the Rockies into Wyoming and the Dakotas at gale force.

These summer westerly wind storms are known as Palousers because they seem to arise in the rolling loess hills of the Palouse.

Palousers happen every summer, in pulses, as warm and cold fronts passing over the PNW interact. Most summers they are mild to strong. Some summers Palousers arise that are near hurricane force.

The windstorm of August 20-21, 1910, blew smoldering fires in the Northern Rockies into a firestorm that incinerated 3 million acres in 48 hours, killed at least 85 people, completely destroyed five towns, and partially destroyed two others, at a time when the region was sparsely populated.

That was a Palouser.

From Pyne, Stephen J., Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910. 2001 Viking Press:

The old-timer was right. The fate of the fire season resided in the swirling dice rolls of the wind. The usual pattern was for cold fronts to ripple across the region every three to five days. In advance of each front, winds would freshen from the southwest, then shift to the northwest after passage. The frontal waves became a vast, slow bellows, drawing in warm, moist air from the south before driving it out with cooler dry air from the north. …The train of fronts that rattled through the Northwest beginning in early July captured this arc of moist air, gulping it in, then exhaling it out. The rhythm of the fronts set the rhythm of the burning.

Each surge of air would stir up old flames and trigger dry lightning storms that kindled new fires. …In the Northern Rockies the approaching fronts drew the winds from the arid Columbia Plains and loess-capped Palouse–thus the Palousers of which the old-timer warned Morris. This was an ancient rhythm. But in 1910 the drought was worse, the storms held more lightning and less rain, the organization sagged from fatigue. The mid-July fire bust strained the Forest Service to its limits. Yet there was no real pause; climax followed climax; the big breakout of 23 July; the flare-ups of 1-2 August, 11-12 August, and 16-17 August; the Big Blowup of 20-21 August. Each built on the last, each fanned little fires into big ones and big ones into conflagrations, until at last a dusting of cold and wet began to dampen them out on 24 August. …

That post was sadly prophetic. The cold front of July 24, 2007, fanned a dozen Let It Burn fires in Idaho and led to the incineration of much of the Payette and Boise National Forests. Over 800,000 acres (1,250 square miles) of forested watersheds were fried [here, here].

What we wrote then still applies:

Big winds plus active fires can lead to regional firestorms. It has happened before. Conditions today are very similar to those in the Summer of 1910, except perhaps that the fuel loadings are much greater, and of course, a few million people live in Idaho and Montana now, with all their homes and stuff.

A regional firestorm today would be one of the most terrible disasters ever to strike in American history. Whatever we can do to avoid it, like putting the fires out [instead of allowing them to burn] and pre-treating the forests and ranges (too late for that this summer), we ought to do.

by YPmule

I like that phrase, roll of the dice. Who gets hit by lightning this time around? Over 60 new fire starts from yesterday’s storm.