Reconstructing Fire Histories in Australia

One line of evidence that confirms historical anthropogenic fire is fire scars on trees. Fire histories are reconstructed by examining stumps and increment cores, and counting the annual rings back to the obvious fire scar years.

But what if trees do not have annual rings? Such is the case in Australia where many trees grow all year round (no annual rings). There are also other trees that are either completely consumed by fires or else exhibit no scarring. Fortunately, there is one type of tree, the grasstree (Xanthorrhoea spp) that flowers only after a fire.

How can that be useful? David Ward and Gerard Van Didden found that grasstrees produce a different concentration of certain chemicals when they flower, and that those chemicals are stored in tree tissues.

Their report, Reconstructing the Fire History of the Jarrah Forest of south-western Australia, is now posted in the W.I.S.E. Colloquium: Forest and Fire Sciences [here].

At the time of the study, David Ward was Senior Research Scientist, Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) in Western Australia and Visiting Senior Research Fellow, Curtin University, Perth. Gerard Van Didden is a retired Department of Conservation and Land Management officer.

Grasstrees [here] look something like cacti but are more closely related to palm trees (both are monocots, the Lily family). Grasstrees only flower after a fire. When they do flower they store unusual levels of lapachol, zinc, magnesium, and copper in their growth rings (lapachol is a compound related to chlorophyll).

Ward and Van Didden were able to show that those growth rings with unusual concentrations of those chemicals indicated a response to known fires. Based on that finding, they were able to reconstruct the fire history of the jarra forest in south-western Australia going back 250 years.

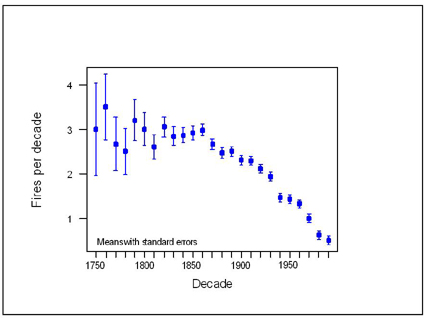

Figure 15: Reconstructed jarrah forest fire history by decade

It is fairly obvious that fire frequency has declined significantly since European settlers took over control of the land from the native Nyoongar people. The amount of lightning has not changed, but fire frequency has dropped from approximately once every 3 years to once every 25 years.

There really is no other explanation for that other than the prior fire regime was anthropogenic. That fact is also supported by pioneer journals and the oral history of the Nyoongar. It is well-known and undeniable that native Australians burned their landscapes frequently, for numerous intentional reasons such as driving game, improving browse for game, encouraging edible plants, preventing fuel build-ups that would lead to catastrophic fires, etc. There is also strong evidence that anthropogenic fire was widely and commonly practiced for as much as 40,000 years (or more) in Australia.

As we say here in the U.S., that’s a long damn time.

Not only was the ancient fire regime anthropogenic, but as a consequence, the entire ecosystem was and is anthropogenic. What is “natural” in Australia is there because of the traditional practices of the residents going so far back into the past that it boggles the mind.

Grasstrees can live for as much as 600 years, so there exists the opportunity to apply Ward’s and Van Didden’s methodology to longer time scales and wider regions. It is almost a given, however, that future researchers will find that the fire frequency has dropped precipitously and concurrently with the elimination of historical anthropogenic fire.