The Roots of Our Forest Health Crisis

The latest addition to the W.I.S.E. Colloquium Forest and Fires Sciences is The Forest Health Crisis: How Did We Get In This Mess? by Charles E. Kay. 2009. Mule Deer Foundation Magazine No.26:14-21 [here].

Dr. Charles E. Kay, Ph.D. Wildlife Ecology, Utah State University, is the author/editor of Wilderness and Political Ecology: Aboriginal Influences and the Original State of Nature [here], author of Are Lightning Fires Unnatural? A Comparison of Aboriginal and Lightning Ignition Rates in the United States [here], co-author of Native American influences on the development of forest ecosystems [here], and numerous other scientific papers.

In this essay, written for a general audience, Dr. Kay recognizes that our forests are in crisis from fire, insects, and disease. He explains that the common cause is too many trees! — which may be surprising to some but is well-known to most forest experts.

Today’s overstocked forests are a-historical; in the past* forests were open and park-like, maintained in that condition by frequent, seasonal, light-burning ground fires. Dr. Kay explains that most of those fires were anthropogenic (human-set).

* By the “past” I mean the entire Holocene and the tail end of the Pleistocene, before which there were very few forests in North America. Instead there was mostly ice or tundra, going back 100,000 years or so.

(Extra: Between 110,000 and 100,000 years ago there was another interglacial, the Eemian. Little is known about the forests of that warm interlude in the Ice Ages. The Ice Ages go back 2.5 million years. For roughly 90 percent of that time, North American forests have been mostly non-existent.)

(Extra Extra: the Ice Ages aren’t over. We passed the peak temperatures about 10,000 years ago. The Earth is headed, inexorably, for another glaciation.)

Human beings arrived in North America at least 13,000 years ago, before the climate had completely shifted and before the great migration northward of plants and animals. Hence humanity preceded most North American forests. Humanity brought fire with them, as well as 150,000 years of practice in how to make and use it. Holocene forests developed under the influence of landscape-scale, human-set fire. Dr. Kay explains that human-set fires, whether intentional of accidental, outnumbered lighting fires by many orders of magnitude.

The forests that arose under the influence of anthropogenic fire were open and park-like, with few trees per acre. Individual trees grew to phenomenal ages; old-growth development pathways were human-induced via frequent burning.

In the absence (over the last 150 years) of frequent, seasonal, anthropogenic fire, rapid “in-growth” has occurred. Thickets of new trees have seeded into the formerly open stands. The increase in tree density has fueled the crisis in forest health. Forests in the past (see * above) were healthier. By healthier I mean less prone to catastrophic fire, insect infestations, and disease epidemics. Today old-growth as well as young-growth trees are rapidly dying from all three factors. Forests are being converted to brushfields.

Restoration forestry does not seek to replicate the past but to learn from it. One lesson of history is that open and park-like forests are healthier. Another is that human stewardship via serious thinning, fuel removal, and subsequent frequent, seasonal, prescribed fire is required to abate our forest health crisis.

The first few paragraphs and some excellent forest photos (click for larger images) from Dr. Kay’s essay are appended below. W.I.S.E. invites you read the entire essay [here]. It is all that and much more.

From The Forest Health Crisis: How Did We Get In This Mess? by Charles E. Kay. 2009. Mule Deer Foundation Magazine No.26:14-21.

THE WEST is ablaze! Every summer large-scale, high-intensity crown fires tear through our public lands at ever increasing and unheard of rates. Our forests are also under attack by insects and disease. According to the national media and environmental groups, climate change is the villain in the present Forest Health Crisis and increasing temperatures, lack of moisture, and abnormally high winds are to blame. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth.

The Sahara Desert, for instance, is hot, dry, and the wind blows, but the Sahara does not burn. Why? Because there are no fuels. Without fuel there is no fire. Period, end of story, and without thick forests there are no high-intensity crown fires. Might not the real problem then be that we have too many trees and too much fuel in our forests? The Canadians, for instance, have forest problems similar to ours but they do not call it a “Forest Health Crisis,” instead they call it a Forest Ingrowth Problem. The Canadians have correctly identified the issue, while we in the States have not. That is to say, the problem is too many trees and gross mismanagement by land management agencies, as well as outdated views of what is natural.

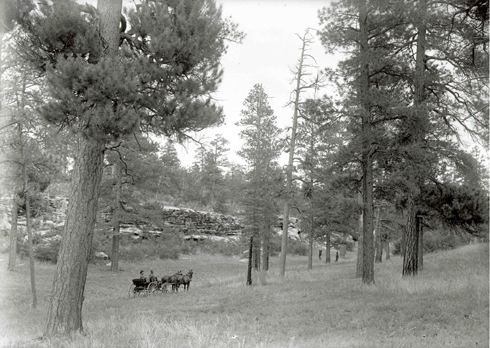

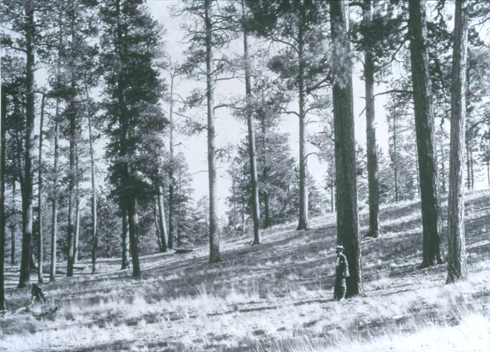

When Europeans first arrived in the West, ponderosa pine forests were open and park-like. You could ride everywhere on horseback or even in a horse and buggy, the forests were so open. On average there were only between 10 and 40 trees per acre with an understory of grasses, forbs, and shrubs. Extensive meadows were also common. In short, ideal mule dear habitat.

Photo 1 — A 1905 photograph of a ponderosa pine forest on the Kaibab in northern Arizona. It is amazing how park-like our pine forests once were. The forests were so open that you could travel virtually anywhere in a horse and buggy. Understory grasses, forbs, and shrubs were abundant. U.S. Geological Survey photo.

Photo 2 — A 1903 photograph of a ponderosa pine forest on the Coconino in northern Arizona. Note the park-like conditions and the men for scale, as well as the abundance of understory forage. Due to the openness of the forest, historically, crown fires never occurred, unlike conditions today. U.S. Forest Service photo.

Photos 6 and 7 — A rare, heritage ponderosa pine forest in southern Utah. This is how ALL the West’s lower-elevation forests should look. A few widely spaced trees with abundant understory forage production. Photos by the author.

Today, however, those same forests contain anywhere from 500 to 2,000 mostly smaller trees per acre. Travel on horseback is out of the question, and access by foot is even difficult. Many former meadows are now overgrown with trees. Understory forage production is approaching zero and our pine forests are becoming increasingly worthless as mule deer habitat.

Photos 3 and 4 — Modern examples of forest ingrowth on the Kaibab National Forest in northern Arizona. The elimination of native burning has allowed a proliferation of small trees. The stage is now set of a high-intensity crown fire. Understory forage production is non-existent. Photos by the author.

Photo 5 — Forest ingrowth on the Dixie National Forest in southern Utah. In the absence of frequent, low-intensity fires, small trees have proliferated setting the stage for a high-intensity crown fire, unlike historic conditions. Understory forage production is non-existent. Photo by the author.

The same thing has happened in other forest types, such as inland Douglas fir, pinyon-juniper, western oaks, sequoias, spruce-fir, and even coastal redwoods, among others. In southern Utah, 1,134 of the repeat photosets that I have made depict conifers and in 92% of those cases, conifers increased, often dramatically. The same is true of pinyon-juniper, which increased in 96% of 1,007 photosets. Every other repeat-photo study that has ever been done in the West has reported similar results. Trees, trees, and more trees. In some forests, such as lodgepole pine, mixed-severity and crown fires were common but not the 100,000 to 200,000 acre infernos we see today.

Why the change? Fire, or more correctly, the lack thereof. Paradoxically, if you want a healthy forest you have to burn it, and frequently. Because bark thickness increases with age, cool-burning surface fires easily kill seedlings and young conifers, but not larger trees. A few seedlings, by chance missed being burned and grew into the widely-spaced trees that greeted Europeans. So historically, western forests burned all the time but there were virtually none of the large-scale, high-intensity crown fires that are all too common today. Instead, frequent, low-intensity surface fires repeatedly thinned the forest preventing ingrowth and the heavy accumulation of fuels. …

by Squanto

“According to the national media and environmental groups, climate change is the villain in the present Forest Health Crisis…”

“Preservationists” who have the government’s ear don’t call it a crisis at all. They keep saying that fires are good and that everything that is occurring today is “natural”. They blame homeowners for living next to National Forests when homes burn. They want to take the 500 year plan to “restore” forests to conditions before the last Ice Age. They somehow ignore 7 million acres of dead forests and massive firestorms.

They will continue to blame dead foresters for what happened 20-50 years ago, warn of rampant clearcutting and huge mill profits. *eyeroll*

Excellent post! The fuel will be cleared one way or the other and unfortunately for us, we are currently letting “the other” way take place.

The 1903 photos are beautiful and it’s a shame what a shambles that same place is today.

Eat a tree-hugger, they’re awfully tasty!