Paralleling Failed Fire Policies with Disastrous Military Strategies

Editor’s note: Roger Underwood is a renowned Australian forester with fifty years experience in bushfire management and bushfire science. He has worked as a firefighter, a district and regional manager, a research manager and senior government administrator. He is Chairman of The Bushfire Front, an independent professional group promoting best practice in bushfire management.

Last March we posted an essay, Australian Bushfire Management: a Case Study in Wisdom Versus Folly by Roger Underwood, in the W.I.S.E. Colloquium: Forest and Fire Sciences [here]. (We have posted other papers by Mr. Underwood, as well, see [here]. The essay also appears in the Fall 2009 issue of Range Magazine [here]).

Mr. Underwood mentions Australian General Sir John Monash in Wisdom Versus Folly. American readers may not be familiar with Sir John. Mr. Underwood writes:

I now realise that I presumed more knowledge of Australian military history than could be expected of any non-Australian. The Monash story is an interesting one from several angles. I jotted down the attached for you this afternoon, hoping it might fill in some gaps. Essentially, what Monash devised was the concept of “combined operations” which came to full fruition in WW2, notably on D-Day. It was Monash’s genius to find a way for the infantry, the artillery, the air force and the tank corps all to work together in a single detailed plan which fused their individual capabilities to best advantage.

Mr. Underwood’s “afternoon jotting” follows:

*****

Monash on the Western Front

By Roger Underwood

In a paper written earlier this year in the wake of the 2009 Victorian bushfire disaster, I drew a pointed analogy. The failed and failing bushfire policies and management strategies in Australia these days have their parallel with the disastrous military strategies adopted by the British Generals in the early years of World War 1. Both were designed to fail, both ignored the lessons of history, and both resulted in inevitable and un-necessary losses of lives.

In my paper I also drew attention to the role played by the Australian General Sir John Monash who engineered the final breakthrough on the western front, having designed and implemented a winning strategy. I called for a new Monash to lead a renaissance in modern Australian bushfire management.

Since then I have been asked several times to explain World War I strategies and Monash’s role. I had taken it for granted that most people understood this stuff. The questions have come especially from Americans who generally lack the intense interest in WW1 history felt by Australians — especially those of about my generation, most of whom had a father, grandfather or uncle who fought and died at the Dardanelles or in Flanders.

The war on the Western Front fell roughly into three phases. The first phase was brief, taking only a few weeks as the German army swept through Belgium and into France, taking all before it. Eventually the British and French dug in and stopped the on-rush. A long “front” resulted, stretching from the North Sea to Switzerland, with the two armies facing each other across a narrow no-man’s land. The second phase was one of a series of largely static and horrible battles, with the British and French flinging themselves repeatedly at the German defences. The position of the front line scarcely changed for three years, while millions of soldiers died. The British Generals knew only one strategy: headlong attack by infantry, following an intense artillery bombardment of the German frontline trenches. In the third and final phase of the war, lasting only a few months in the second half of 1918, the British adopted a new strategy and swept eastward, massacring the Germans. By this time America had entered the War and was providing fresh troops and materiel –- the Germans saw the writing on the wall and negotiated an Armistice. The critical thing to me was that it was an Australian who engineered the new strategy, and Australian, New Zealand and Canadian troops who largely provided the strike troops to implement it.

Australians had started arriving at the western front in late 1915 following the withdrawal from the disastrous Gallipoli campaign. Although the Australians had their own field commanders, those field commanders reported to British Generals and the British Commander in Chief Field Marshal Haig. This highly unpopular arrangement was the result of some political argy-bargy between the British and Australian governments. It meant that in 1916 and 1917, Australian troops were forced to follow the British strategy, i.e., attack at all costs against well-defended positions and hardened German troops with expertise in the use of enfilading machine gun fire. Consequently Australian infantry suffered shocking losses on the killing fields at Passchendael, Fromelle, Pozieres, Villers-Bretonneux and Messine Ridge. By the time of the battle of Hamel, however, some changes had been made. Both the Canadian and Australian governments were fed up with the appalling generalship of the British Army and insisted on leadership changes. Amongst other things this led to the appointment of the first Australian to lead the Australian Army: General Sir John Monash.

Monash was born in 1865 in Victoria, the son of Jewish Prussian immigrants. He was a “Renaissance Man”, with degrees in arts, engineering and law from Melbourne University and was a brilliant mathematician. He became a civil engineer but also, in his spare time, an artillery commander in the Victorian militia. By the time of the Gallipoli landing in April 1915 he had joined up, was a full Colonel in the regular army and commander of the 4th Infantry Brigade. He led the 3d Australian Division on the western front throughout 1917 and was then put in full charge of the entire Australian Army Corps in early 1918. He was by then, in his early 50’s, a very experienced and battle-hardened front-line soldier.

Monash deplored the strategy of the British generals. He noted that it always failed. Moreover, he could see no chance of it ever succeeding. Firstly, the battles had no surprise element. The British artillery would pound the German front lines for days before an attack, but the Germans simply retreated into deep, bomb-proof bunkers, from which they emerged to set up their defensive wall the moment the bombardment stopped. Then, even if by superhuman effort and sheer weight of numbers the attackers got into the enemy’s front line, the Germans had fresh reserves behind the line who would counter-attack, catching the exhausted attackers in trenches whose defences faced the wrong way.

The two essences of the Monash strategy were meticulous planning and collaborative arrangements between the various service arms. He did away with the massive pre-attack bombardments, instead using a superbly-managed “rolling barrage” which crept toward the enemy in front of the advancing attackers. He used intelligence to determine the exact location of the enemy artillery, and focused on knocking them out by precision gunnery the moment the battle commenced. He championed the new offensive weapons, in particular the tank, and insisted on joint planning and coordination between his tank and infantry commanders (something that seems elementary today, but he was the first to do it; indeed many of Monash’s senior officers distrusted or were contemptuous of the tank, preferring horse-mounted cavalry). He also developed close coordination with the Air Force, and used aircraft to bomb and strafe the German troops in the reserve trenches to prevent the inevitable counter-attacks.

Most innovatively, he used aircraft to re-supply his advancing troops. In the past, the attackers had often found themselves short of ammunition, water, grenades etc after they had achieved their objective and were then subjected to counter-attack. Monash arranged for special supply drops from low flying aircraft. Again this seems elementary, but until Monash organised it, the Air Force and the Army had operated almost completely independently.

Finally, Monash had his sights set well beyond the enemy’s front line trenches. He identified important objectives kilometres further on, and he organised tanks and armoured cars with supporting infantry to move rapidly through the first line of defences and support trenches and, leap-frogging each other with successive waves, to take key offensive positions beyond. It was a concept of mobile, not static warfare, and was the product of a colossal planning effort and intricate control systems.

Monash had been a musician in his former life, and was a lover of classical music. Not surprisingly he chose a musical analogy to describe his battle strategy. He saw the cooperative arrangements between infantry, artillery, tanks and aircraft, planned down to the last minute detail, as “an orchestral composition” in which each instrument made its entry at the right moment and played its phrases to a score, all contributing to the final harmonious result.

Monash first played his symphony at the small-scale battle of Hamel (all over in 90 minutes of exquisite execution of a brilliant plan), and the result so amazed the Generals back at HQ, they allowed him to elaborate upon it. This resulted in a series of stunning victories, culminating (in August, 1918) in the smashing of the Hindenburg Line, up until then the great stumbling block of the Western Front. It was a dramatic victory; the stalemate collapsed, the front was riven. It signified the end of the war –- the German Army never recovered and were virtually on the run when the Armistice was signed on November 11th, 1918.

Throughout all of this, Monash was also fighting personal battles. He suffered serious prejudice through being a Jewish colonial militiaman of German parentage. He was looked down upon by the top brass because he was an educated and scholarly man who was not a professional soldier but had come up through the ranks. He led Australian soldiers who, although acknowledged as tough and savage fighters, were regarded as ‘unsoldierly’ by the pom Generals. Australian soldiers, for example, refused to salute English officers; they were great drinkers and looters, and going into battle would dress to fight, not for the parade ground. It is characteristic that there was only ever one mutiny of Australian troops during World War 1 –- this was over a proposed restructure of the battalions, with which the troops did not agree. The restructuring had been forced on Monash from above, and he had resisted it, but in the end was over-ruled. Although they refused to be restructured, the men did not refuse to fight, electing their own officers from within the ranks to lead them until the mess was sorted out.

Right into 1918 there were political machinations going on in London to undermine Monash. They were led by a cabal of journalists and war correspondents who regarded Monash as “too pushy, too ambitious and too clever”. At least one of these journalists had the 1918 equivalent of a hotline back to the Prime Minister in Australia. It is a great tribute to Monash that he could put all of this out of his mind and concentrate on the job at hand. The great war historian Lidell Hart summed up the situation, “A war-winning combination had been found: a corps commander of genius, the Australian infantry, the Tank Corps, the Royal Artillery and the RAF.” Despite this, and the fact that his troops revered him, Monash was never lionized in the press. He was not a man to court favour with journalists, and this cost him their support, both during the war and afterwards.

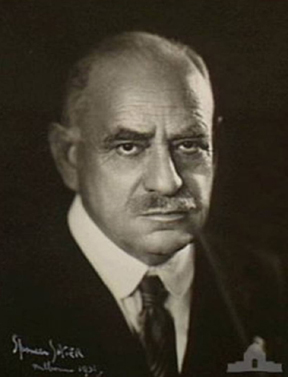

Portrait of Sir John Monash in the Australian War Memorial, painted just after the War.

Following the war, Monash was involved in a number of engineering and civic projects in Victoria and in looking after ex-servicemen. He aspired to national politics or national leadership of some sort, but the same media and political forces that had sought to undermine him during the war lined up against him again. But when he died in 1931 he was not forgotten by his former troops or their families. An estimated 250,000 came to his funeral to pay their respects. Such numbers had never been seen before, or since, at any funeral in this country.

Postscript

It is, of course, fantasy on my part to imagine a Monash-like figure arising in Australia to tackle and resolve our bushfire crisis. The vested interests of the political parties, the public service, the fire services, academia, and the environmental organisations would never allow him the opportunity, let alone the power, to take charge, set up a winning strategy and see it through. He would first be undermined, and then destroyed. The crisis of war, or of perhaps armed insurrection, both of which represent the ultimate breakdown of good government, seem to provide the only forum these days in which true leaders can truly lead.

Roger Underwood - August 2009