Deer, Elk, Bison Population Dynamics Research Methods Wildlife Management

by admin

Comments Off

The Art and Science of Counting Deer

Charles E. Kay. 2010. The Art and Science of Counting Deer. Muley Crazy Magazine, March/April 2010, Vol 10(2):11-18

Full text:

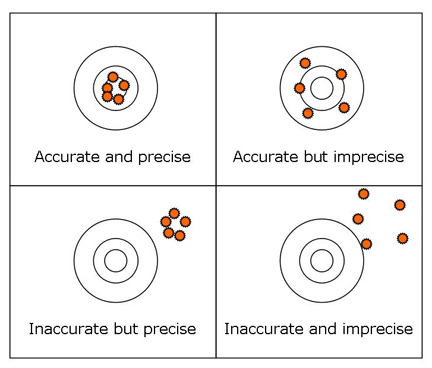

It is the simplest of questions and upon which all management is based. It is also the first thing most hunters want to know. How many deer are there? The answer? Well, there are no answers, only estimates. In addition, one needs to understand the difference between precision and accuracy. Think of precision as shooting a five-shot, half-inch group at 100 yards, but the group is 20 inches high and to the right. The shots have been very precise, almost in the same hole, but they were not accurate because they were far from the center of the target. Accuracy is hitting the bullseye. So, an estimate can be precise without being accurate. Estimates that are both precise, low variation, and accurate, close to the true number, are very difficult and very expensive to obtain. Moreover, all population estimates contain assumptions, as well as sampling errors and statistical variation.

Since the advent of modern game management, various methods have been developed to count wildlife. Entire books have been written on the subject and there are enough scientific studies to fill a small library. Here, I will discuss only the techniques that have been, or are commonly used to estimate the number of mule deer and elk on western ranges. This includes ground counts, aerial surveys, population models, pellet-group counts, and thermal imaging.

The oldest and simplest method is ground counts. As the name implies, these are simply counts conducted on foot, horseback, or from vehicles by either one or more observers. While relatively inexpensive, this method is neither precise nor accurate. There is the problem of double counting when the deer run over the hill into the next canyon that has not yet been surveyed and under counting when animals are hidden from view by vegetation or topography. Today, ground counts are seldom used to estimate herd numbers but they are still commonly employed to estimate fawn:doe ratios or buck:doe ratios under the assumption that doe, fawn, and buck sighting rates are similar, which they are not. If bucks are more difficult to see than does because of the habitat the males occupy, or their behavior, ground counts will underestimate the number of bucks.

Due to the shortcomings of ground counts, wildlife biologist were quick to take to the air, first in airplanes and later in rotary aircraft. To make a long story short, counts from helicopters are more accurate than population surveys from fixed-wings. Any aerial count, though, is subject to errors, because even from the air you do not see all members of a population, be they mule deer or elk. This is what, in the scientific literature, is known as sightability bias. Even in experiments where livestock have been placed in flat, grassy pastures, aerial observers fail to record all the animals.

Lessons from a Transboundary Wolf, Elk, Moose and Caribou System

Mark Hebblewhite. 2007. Predator-Prey Management in the National Park Context: Lessons from a Transboundary Wolf, Elk, Moose and Caribou System. Predator-prey Workshop: Predator-prey Management in the National Park Context, Transactions of the 72nd North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Introduction

Wolves (Canis lupus) are recolonizing much of their former range within the lower 48 states through active recovery (Bangs and Fritts 1996) and natural dispersal (Boyd and Pletscher 1999). Wolf recovery is being touted as one of the great conservation successes of the 20th century (Mech 1995; Smith et al. 2003). In addition to being an important single-species conservation success, wolf recovery may also be one of the most important ecological restoration actions ever taken because of the pervasive ecosystem impacts of wolves (Hebblewhite et al. 2005). Wolf predation is now being restored to ecosystems that have been without the presence of major predators for 70 years or more. Whole generations of wildlife managers and biologists have come up through the ranks, trained in an ungulate- management paradigm developed in the absence of the world’s most successful predator of ungulates—the wolf. Many questions are now facing wildlife managers and scientists about the role of wolf recovery in an ecosystem management context. The effects wolves will have on economically important ungulate populations is emerging as a central issue for wildlife managers. But, questions about the important ecosystem effects of wolves are also emerging as a flurry of new studies reveals the dramatic ecosystem impacts of wolves and their implications for the conservation of biodiversity (Smith et al. 2003; Fortin et al. 2005; Hebblewhite et al. 2005; Ripple and Beschta 2006; Hebblewhite and Smith 2007).

In this paper, I provide for wildlife managers and scientists in areas in the lower 48 states (where wolves are recolonizing) a window to their future by reviewing the effects of wolves on montane ecosystems in Banff National Park (BNP), Alberta. Wolves were exterminated in much of southern Alberta, similar to the lower 48 states, but they recovered through natural dispersal populations to the north in the early 1980s, between 10 and 20 years ahead of wolf recovery in the northwestern states (Gunson 1992; Paquet, et al. 1996). Through this review, I aim to answer the following questions: (1) what have the effects of wolves been on population dynamics of large-ungulate prey, including elk (Cervus elaphus), moose (Alces alces) and threatened woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus tarandus), (2) what other ecosystem effects have wolves had on montane ecosytems, (3) how sensitive are wolf-prey systems to top-down and bottom-up management to achieve certain human objectives, and (4) how is this likely to be constrained in national park settings? Finally, I discuss the implications of this research in the context of ecosystem management and longterm ranges of variation in ungulate abundance. …