Clam Gardens

Williams, Judith. Clam Gardens: Aboriginal Mariculture On Canada’s West Coast. 2006. New Star Books LTD

Pre-Contact West Coast indigenous peoples are commonly categorized in anthropological literature as “hunter gatherers”. However, new evidence suggests they cultivated bivalves in stone-walled foreshore structures called “clam gardens” which were only accessible at the lowest of tides. Judith Williams journeyed by boat around Desolation Sound, Cortes and Quadra Islands and north to the Broughton Archipelago to document the existence of these clam gardens. The result is a fascinating book that bids to change the way we think about West Coast aboriginal culture. — from the back cover

Clam Gardens is a delightful little book, written by an artist and resident of the British Columbian archipelago. A native friend told her about the clam gardens, she investigated them, and “re-discovered” a complex maritime aquaculture of great antiquity. After years of study and pestering of university anthropologists, Judith Williams finally convinced them that the vast network of coastal clam beds from Puget Sound to the Queen Charlotte Islands were largely anthropogenic.

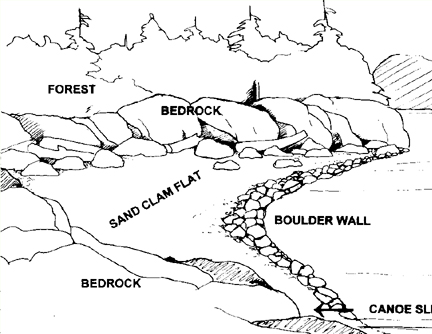

Native people had not only dug natural clam habitat, but, in favourable locations around the Broughton islands, had erected a complex of rock-walled terraces that suggest what we call mariculture.

Bringing these Native mariculture structures to light may be termed, by some, a “discovery,” although the clam gardens, as will be shown, were never lost. Given the evidence of Native knowledge and usage that has also come to light, it’s prudent to sidestep that term. Let’s just say that the story of the re-emergence of these rock structures makes visible to the non-Native world a mindset-altering number of boulder walls, which were erected by Northwest Coast indigenous people at the lowest level of the tide to foster butter clam production. The number of gardens, their long usage, and the labour involved in rock wall construction indicate that individual and clustered clam gardens were one of the foundation blocks of Native economy for specific coastal peoples.

———————————————————————————————-

The Northwest Coast Indians did not need convincing, since they had been building, maintaining, and utilizing the clam gardens for thousands of years. The cultivated landscapes of native North America were not confined to dry land, as Clam Gardens so enjoyably reveals.

The Vegetation of the Willamette Valley

Johannessen, Carl L. , William A. Davenport, Artimus Millet, Steven McWilliams. The Vegetation of the Willamette Valley. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 61 (2), 286–302. 1971.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

ABSTRACT: The vegetation of the Willamette Valley, Oregon, has been modified by man for centuries. Thc earliest white men described the vegetation as extensive prairies maintained by annual fires set by Indians. The cessation of burning in the 1850s allowed expansion of forest lands on the margins of the former prairies. Today some of these forest lands have completed a cycle of growth, logging, and regrowth. Much of the former prairie is now in large-scale grain and grass seed production and is still burned annually. The pasture lands of the Valley are still maintained as open lands with widely scattered oaks. KEY WORDS: historical vegetation, Indian burning, prairies, vegetation change, Willamette Valley.

The vegetation of the Willamette Valley, Oregon, has changed significantly under human influence. The Indians of this area, at the time of contact with white settlers, set prairie fires annually, which created a prairie/open woodlands complex. The new settlers, who increased rapidly in the mid-nineteenth century, forced the Indians to leave. Their practice of annual burning was temporarily discontinued. White settlers brought modifications of the habitat with their livestock and cropping, and more recently, forestry systems…

The fire-tolerant, widely-spaced oak, fir, or pine seeded the so-called openings to form thickets that have grown to dense woodlands and forest. Firs now dominate these woodlands, because the firs are able to continue vertical growth and reach light more effectively than the broadleaf trees. A complete cycle has occurred in some locations. Mature 70 to 100-year-old fir trees have been harvested from formerly open prairie and parkland, and now new crops of seedlings

have invaded the logged-over areas…

The Long Tom and Chalker Sites

O’Neill, Brian L. , Thomas J. Connolly, and Dorothy E. Freidel, with contributions by Patricia F. McDowell and Guy L. Prouty. A Holocene Geoarchaeological Record for the Upper Willamette Valley, Oregon: The Long Tom and Chalker Sites. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers 61, Published by the Museum of Natural History and the Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon, Eugene. 2004.

Abstract:

Data recovery investigations at two prehistoric sites were prompted by the Oregon Department of Transportation’s realignment of the Noti-Veneta segment of the Florence to Eugene Highway (OR 126) in Lane County, Oregon. The Long Tom (35LA439) and Chalker (35LA420) archaeological sites are located on the floodplain of the Long Tom River in the upper Willamette Valley of western Oregon. Investigations at these sites included an examination of the geomorphic setting of the project to understand the processes that have shaped the landscape and to which its human occupants adapted. The cultural components investigated ranged in age between about 10,000 and 500 years ago.

Geomorphic investigation of this portion of the Long Tom River valley documents a landform history spanning the last 11,000 years. This history is punctuated by periods of erosion and deposition, processes that relate to both the preservation and absence of archaeological evidence from particular periods. The identification of five stratigraphic units, defined from trenching and soil coring in the project area, help correlate the cultural resources found at sites located in the project. Stratigraphic Unit V, found at depths to approximately 250 cm, is a clayey paleosol with cultural radiocarbon ages between 11,000 and 10,500 cal BP. Unit N, with radiocarbon ages between approximately 10,000 and 8500 cal BP, consists of fine-textured sediments laid down during a period of accelerated deposition. An erosional unconformity separates Unit IV from the overlying Unit III. In the archaeological record, this unconformity represents a gap of nearly 3000 years, from 8500 to 5700 cal BP, and corresponds to a period of downcutting in the Willamette system that culminated with a transition from the Winkle to Ingram floodplain surfaces. Unit III sediments are sandy loams within which are found numerous oven features at the Long Tom, Chalker, and other nearby archaeological sites, and date between approximately 5700 to 4100 years ago. A near absence of radiocarbon-dated sediments in the project area between approximately 4100 and 1300 years ago suggests either a lack of use of this area during this period, or an erosional period that was apparently less severe on a regional scale. Units II and I are discontinuous bodies of vertically accreted sediments which represent a period of rapid deposition in the project area during the last 1300 years. It is estimated that Unit I sediments were deposited within the last 500 years.

Investigations at the Long Tom site discovered three cultural components. Components 1 and 3 are ephemeral traces of human presence at the site. The Late Holocene-age Component 1, found within Stratigraphic Units I and II, contains a small assemblage of chipped stone tools and debitage dominated by locally obtainable obsidian. The Early Holocene-age Component 3 contains a single obsidian uniface collected from among a scatter of fire-cracked rock and charcoal found within Stratigraphic Unit IV. Charcoal from this feature returned a radiocarbon age of 9905 cal BP. Contained within Stratigraphic Unit III, Component 2 presents evidence for a concentrated period of site use between approximately 5000 and 4000 cal BP. Geophysical exploration of the deep alluvial sediments with a proton magnetometer located magnetic anomalies, a sample of which was mechanically bisected and hand-excavated for closer analysis. A total of 21 earth ovens and two rock clusters was exposed in sediments associated with radiocarbon ages clustering about 4400 cal BP. Charred fragments of camas bulbs and hazelnut and acorn husks were recovered from the ovens. Few tools were discovered in their vicinity. Larger-scale excavations within the Middle Holocene sediments at the west end of the site discovered what is interpreted as a residential locus.

The Standley Site

Connolly, Thomas J., with contributions by Joanne M. Mack, Richard E. Hughes, Thomas M. Origer, and Guy L. Prouty. The Standley Site (35D0182): Investigations into the Prehistory of Camas Valley, Southwest Oregon. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers No. 43. Published by the Department of Anthropology and Oregon State Museum of Anthropology University of Oregon, Eugene, October 1991.

Abstract:

The Standley site (35D0182) is located at the southern edge of Camas Valley, a small basin on the upper Coquille River of southwestern Oregon. The earliest radiocarbon date from the site is 2350 ± 80 years ago, but obsidian hydration analysis suggests that initial occupation may have begun between 4500 and 5000 years ago. Both obsidian hydration and radiocarbon evidence suggest that occupation was most intense and continuous between 3000 and 300 years ago.

Cultural patterns at the Standley site are unclear at both ends of this occupation span; the remains of the earliest use episodes were disturbed by later prehistoric occupations, and the upper levels of the site were severely disturbed by historic activity. Radiocarbon evidence for the latest occupation period (within the last 500 years) includes dates from the basal portions of posts preserved in the lower levels of the site. The best preserved cultural patterns at the site, presumed to be associated with a set of radiocarbon dates ranging from 1180 to 980 years ago, are within a relatively rock-free area in the north-central portion of the main excavation block. Distinct artifact clusters, and possible structural remains, are present within this area.

The large size of the Standley site, the possible presence of structures, and the variety and density of artifact types present-including an enormous array of chipped stone tools, hammers and anvils, edge-ground cobbles, abrading stones, pestles, stone bowls, clay figurines, painted tablets, and exotic material such as schist, pumice, and steatite-indicate that the site served as a substantial encampment of some duration. There was some evidence for structural remains (posts and bark), but no clear evidence for semisubterranean housepits such as those reported elsewhere in southwest Oregon. The presence of charred hazelnuts and camas bulbs suggest a probable summer-to-fall occupation.

Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest

Boyd, Robert, editor. Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. 1999. Oregon State University Press.

Selected excerpts:

Robert Boyd — Introduction

In May and June of 1792, George Vancouver’s British-sponsored, exploring expedition entered the uncharted waters of Puget Sound.1 Expecting a forested wilderness inhabited by unsophisticated natives, they were surprised at what they found. At Penn Cove, on Whidbey Island:

“The surrounding country, for several miles in most points of view, presented a delightful prospect consisting chiefly of spacious meadows elegantly adorned with clumps of trees; among which the oak bore a very considerable proportion, in size from four to six feet in circumference. In these beautiful pastures … the deer were seen playing about in great numbers. Nature had here provided the wellstocked park, and wanted only the assistance of art to constitute that desirable assemblage of surface, which is so much sought in other countries, and only to be acquired by an immoderate experience in manual labour.”

Among the “pine forests” of Admiralty Inlet, Joseph Whidbey noted “clear spots or lawns … clothed with a rich carpet of verdure.” The “verdure” of these “lawns” included “grass of an excellent quality,” tall ferns “in the sandy soils” and several other plants: “Gooseberrys, Currands, Raspberrys, & Strawberrys were to be found in many places. Onions were to be got almost everywhere.” Whidbey was nostalgic: the lawns had “a beauty of prospect equal to the most admired Parks of England.”

Nearly two centuries later, in 1979, well after the “lawns” observed by Vancouver’s party had been converted to agriculture, the “pine forests” partially cut and managed for timber production, many indigenous species supplanted by Eurasian varieties, and the villages and seasonal camps of the Native Americans replaced by the cities and farms of Euro-American newcomers, anthropologist Jay Miller went into the Methow Valley [north-central Washington] with a van load of [Methow Indian] elders, some of whom had not been there for fifty years. When we had gone through about half the valley, a woman started to cry. I thought it was because she was homesick, but, after a time, she sobbed, ‘When my people lived here, we took good care of all this land. We burned it over every fall to make it like a park. Now it is a jungle. Every Methow I talked to after that confirmed the regular program of burning.

Separated by 187 years of systemic, region-wide ecological change in the Pacific Northwest, these two sets of observations address several themes central to this volume. The Pacific Northwest at first contact with Euro-Americans was not exclusively a forested wilderness. West of the Cascades, as documented in the Vancouver journals, there were large and small prairies scattered throughout a region that was climatically more suited to forest growth. And east of the mountains, as the Methow passage suggests, the forests of the past were quite different, with a minimum of underbrush and clutter. Other differences in local environments were present both east and west.

Vancouver believed that “Nature” alone was responsible for the “luxuriant lawns” and “well-stocked parks”; there is nothing in any of the expedition’s journals suggesting that the Native inhabitants of the “inland sea” had any hand in their existence. Until relatively recently, most anthropologists believed this as well. The traditional stereotype of non-agricultural foraging peoples was that they simply took from the land and did not have the tools or knowledge to modify it to suit their needs. We now know better. Indigenous Northwesterners did indeed have a tool-fire-and they knew how to use it in ways that not only answered immediate purposes but also modified their environment. We now know that the “lawns” that Vancouver observed on Whidbey Island, the prairies that early trappers and explorers described in the Willamette Valley, and the open spaces that led the Hudson’s Bay Company to select the site of Victoria for their headquarters in 1845 had been actively manipulated and managed, if not actually “created,” by their Native inhabitants. Anthropogenic (human-caused) fire was by far the most important tool of environmental manipulation throughout the Native Pacific Northwest.

Native American Influences on the Development of Forest Ecosystems

Thomas M. Bonnicksen, M. Kat Anderson, Henry T. Lewis, Charles E. Kay, and Ruthann Knudson. 1999. Native American influences on the development of forest ecosystems. In: Szaro, R. C.; Johnson, N. C.; Sexton, W. T.; Malk, A. J., eds. Ecological stewardship: A common reference for ecosystem management. Vol. 2. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science Ltd: 439-470.

Selected excerpts:

I INTRODUCTION

Ecosystem management cannot succeed in promoting stewardship if it fails to recognize that humans are an integral and natural part of the North American landscape. Ecosystem management has the potential for widening the gap between people and nature. Subdividing landscapes into ecosystems could create the false impression that ecosystems are real things. This illusion becomes more dangerous when people think that they live on the outside and nature exists on the inside of ecosystems.

Biologists developed the ecosystem model to describe physical, chemical, and biological interactions at a particular time within an arbitrarily defined volume of space (Lindeman 1942). They usually exclude people because the boundaries are sometimes drawn around small parts of the landscape, such as watersheds. Because management decisions come from outside, ecosystems appear as separate entities. Therefore, ecosystem management may reinforce the myth that nature exists apart from people if it does not explicitly state otherwise.

A corollary myth assumes that climate dictated the structure and function of ecosystems. On the contrary, climate provides either a favorable or unfavorable physical environment for certain plants to grow. It does not dictate which plants grow in that environment. Similarly, climate does not dictate human behavior. It only sets temporary limits. Human innovations in technique and technology can and do push back those limits. Therefore, climate is not the sole determinant nor even in many cases the dominate force in guiding the development of particular ecosystems. American Indians selectively hunted, gathered plants, and fired habitats in North America for at least 12,000 years. Unquestionably, humans played an important role in shaping North America’s forest ecosystems.

Interpretations of the impacts made by indigenous people in North America are largely limited to what can be postulated in terms of paleontological, anthropological, and archaeological evidence. None of these approaches have been completely persuasive to skeptics who require more substantial and corroborative evidence before accepting the significance of the environmental changes induced over 12,000 or more years by hunting-gathering societies and, for the last 2,000 years, by indigenous farmers as well. Taken together, however, the evidence shows a clear and convincing pattern of indigenous human influences on prehistoric, historic, and contemporary ecosystems.