Climate Changes and their Effects on Northwest Forests

Schlichte, Ken. 2010. Climate Changes and their Effects on Northwest Forests. Northwest Woodlands, Spring 2010.

Ken Schlichte is a retired Washington State Department of Natural Resources forest soil scientist. Northwest Woodlands Magazine [here] is a quarterly publication produced in cooperation with woodland owner groups in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Climate changes are always occurring, for a variety of reasons. Climate changes were responsible for the melting and retreat of the Vashon Glacier back north into Canada at the beginning of the postglacial Holocene Epoch around 11,000 years ago. Climate changes were also responsible for the warmer temperatures of the Holocene Maximum from around 10,000 to 5,000 years ago, the warmer temperatures of the Medieval Warm Period around 1,000 years ago and the coldest temperatures of the Little Ice Age during the Maunder Minimum around 300 years ago. These climate changes, the reasons for them and their effects on our Northwest forests are discussed below.

Forests soon became established on the glacial soil deposits left by the retreat of the Vashon Glacier, but some of these forests were later replaced by prairies and oak savannahs as temperatures increased during the Holocene Maximum. …

Forests began advancing into the South Puget Sound area prairies and replacing them as temperatures began decreasing following the Holocene Maximum. Native Americans began burning these prairies in order to maintain them against the advancing forests for their camas-gathering and game-hunting activities. Forest replacement of these and other Northwest prairies has proceeded rapidly since the late-1800s in the absence of these burning activities. …

The warmer temperatures and increased solar activity of the Medieval Warm Period were followed by a period of cooler temperatures and reduced solar activity known as the Little Ice Age. The coldest temperatures and lowest solar activity of the Little Ice Age both occurred during the Maunder Minimum from 1645 to 1715… The Dalton Minimum was a period of lower solar activity and colder temperatures from 1790 to 1820. Mount Rainier’s Nisqually Glacier reached a maximum extent in the last 10,000 years during the colder temperatures of the Maunder Minimum and the Dalton Minimum and then began retreating as Northwest temperatures warmed following the mid-1820s and the Dalton Minimum. Beginning in 1950 and continuing through the early 1980s the Nisqually Glacier and other major Mount Rainer glaciers advanced in response to the relatively cooler temperatures and higher snowfalls of the mid-century, according to the National Park Service. …

Fuel treatments, fire suppression - Warm Lake

Graham, Russell T.; Jain, Theresa B.; Loseke, Mark. 2009. Fuel treatments, fire suppression, and their interaction with wildfire and its impacts: the Warm Lake experience during the Cascade Complex of wildfires in central Idaho, 2007. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-229. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 36 p.

Full text [here] (9.3MB)

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

Wildfires during the summer of 2007 burned over 500,000 acres within central Idaho. These fires burned around and through over 8,000 acres of fuel treatments designed to offer protection from wildfire to over 70 summer homes and other buildings located near Warm Lake. This area east of Cascade, Idaho, exemplifies the difficulty of designing and implementing fuel treatments in the many remote wildland urban interface settings that occur throughout the western United States. The Cascade Complex of wildfires burned for weeks, resisted control, were driven by strong dry winds, burned tinder dry forests, and only burned two rustic structures. This outcome was largely due to the existence of the fuel treatments and how they interacted with suppression activities. In addition to modifying wildfire intensity, the burn severity to vegetation and soils within the areas where the fuels were treated was generally less compared to neighboring areas where the fuels were not treated. This paper examines how the Monumental and North Fork Fires behaved and interacted with fuel treatments, suppression activities, topographical conditions, and the short- and long-term weather conditions.

Introduction

The Payette Crest and Salmon River Mountain ranges of central Idaho create rugged and diverse landscapes. The highest elevations often exceed 10,000 ft with large portions ranging from 5,500 to 6,500 ft above sea level. The Salmon River and its tributaries dissect these mountains creating an abundance of steep side slopes. The South Fork of the Salmon River, with its origin within the 6,000- to 7,000-ft mountains east of Cascade, Idaho, flows north until it joins the main Salmon at an elevation of 2,100 ft. At 5,300 ft, the Warm Lake Basin near the South Fork’s origin is one of the many large and relatively flat basins that occur in central Idaho (Alt and Hyndman 1989; Steele and others 1981) (fig. 1). …

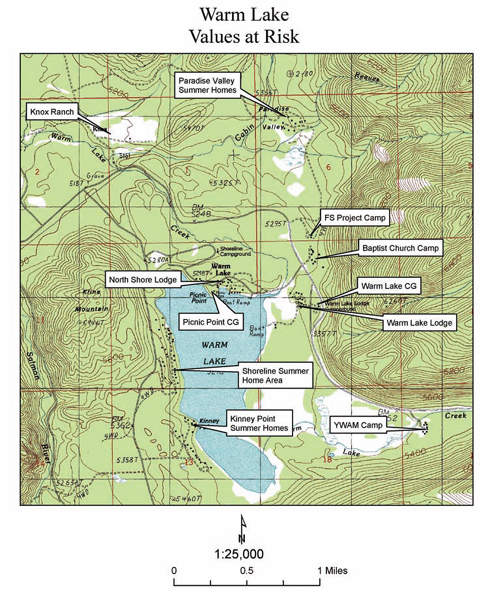

Forest Treatments in the Wildland Urban Interface Near Warm Lake

A large proportion (>66%) of Idaho lands are owned and/or administered by state and federal governments (NRCM 2008). In addition, there are over 30,000 residences located on lands in the wildland urban interface (WUI) with many of these residences being on lands leased from state or federal governments. Valley County, located in the central part of the Idaho, has over 2,200 residences located in the WUI with a concentration of structures near Warm Lake (Headwaters Economics 2007) (fig. 1). Within the Warm Lake area, approximately 20 miles northeast of Cascade, there are roughly 70 residences and other structures (fig. 3). In addition to the summer homes, the area contains two commercial lodges, two organizational camps, and a Forest Service Project Camp. The Warm Lake Basin is the headwater for the Salmon River, which is home to both Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchu tshawytscha) and steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Both species are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, which highlights the Salmon River’s ecological and commercial value. Because of these threatened species, the amount of vegetative manipulation occurring within the Salmon River drainage since the mid-1970s has been minimal (USDA Forest Service 2003).

Figure 3. Several homes, lodges, camp grounds (CG), Forest Service camps (FS), and other developments are located within the Warm Lake area of central Idaho. Click map for larger image.

Baden-Powell and Australian Bushfire Policy

By Roger Underwood

Editor’s Notes: This essay is one in a series (circulated to colleagues on the Internet, but unpublished) which examines reports, letters, stories and anecdotes from early volumes of The Indian Forester, the principal forestry journal of India since 1880.

Baden Henry Baden-Powell (1841-1901) entered the Bengal Civil Service at the age age of 20 and eventually became a Judge of the Chief Court of the Punjab and India’s first Inspector-General of Forests. He was among the first to bring European forestry to India. B. H. Baden-Powell was the son of Rev. Baden Powell (1796–1860), an English mathematician and Church of England priest, and brother of Robert Baden-Powell (1857-1941), the founder of the Boy Scouts.

Author Roger Underwood is a former General Manager of the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) in Western Australia, a regional and district manager, a research manager and bushfire specialist. Roger currently directs a consultancy practice with a focus on bushfire management and is Chairman of The Bushfire Front Inc.. He lives in Perth, Western Australia.

—-

IN AN EARLY chapter in these chronicles we met Baden Henry Baden-Powell, joint-founding editor of The Indian Forester, and later the Inspector-General of Forests (chief of the Forest Service) in India during the early 1870s. I have again been dipping into his wonderful journal, and have found to my intense interest a long article by Baden-Powell himself.

The article is based on a tour of inspection of the forests of Dehra Doon [1] in early 1875. It is interesting from many perspectives. In the first place, it was written at a time when formal forest management was being first introduced in what was then ‘British India’. The Indian Forest Service had only recently been created, and its tiny staff of European-trained foresters was trying to overlay European concepts of forest administration and management onto forests that had been, mostly, commonage for thousands of years. The concepts were visionary in terms of forest conservation and protection and in ensuring a sustainable yield of timber, but they imposed restrictions and constraints on rural Indians that were intensely unpopular.

The article also provides an insight into the attitude to fire held by the colonial foresters who occupied senior positions in the Indian Forest Service. These attitudes are especially intriguing because they were later imported into Australia when our first Forests Departments were being established around the time of World War I. Here they persisted up until the early 1950s, before being largely abandoned. Fascinatingly, however, they have resurfaced in the 1990s, this time embraced by environmentalists and a new generation of academic ecologists. To this day, the European/colonial attitudes to forest fire which were articulated in India in the 1870s continue to influence Australian land management — especially for national parks in NSW and Victoria — and also the approach to bushfire control adopted by our fire and emergency services.